Polish the rice. Wait, what?

Regular Saké vs. Premium Saké

Why Less Can Be More

Saké Grades and Rice Polishing Ratio

Rice is the main fermentable ingredient used to brew saké, and it’s often considered the single most important ingredient.

One of the major differences between the various grades or classifications of saké is related to the rice-polishing ratio, or seimaibuai (pronounced “say-my-boo-eye”).

Rice is milled or “polished” before being used in brewing to eliminate the fats, proteins, and minerals on the outer portions of the grain that can inhibit fermentation and cause off flavors in the finished product. In general, the more the rice has been polished, the more refined and elegant the saké’s flavor profile will be.

The seimaibuai is expressed as a percentage representing the amount of the original rice grain that remains after polishing. As a point of reference, the white table rice with which we are all familiar has usually had 10% of the outer portion polished away, so its seimaibuai is 90%.

Around 74% of all saké produced in Japan is futsushu, “ordinary” or “table” saké, and this is the type of saké (served hot, Hot, HOT!) that most people in the U.S. encounter for the first time at their local Japanese restaurant. The rice used in making this saké has a seimaibuai of less than 70%, meaning less than 30% of the original grain has been polished away.

At Saké Nomi, we specialize in premium saké, which makes up the remaining 26% of saké produced in Japan. In Japanese, this grouping of saké classifications is referred to as tokutei meishoushu, or “special designation saké.”

To be designated as a premium saké, the rice used to brew the saké must have a seimaibuai of 70% or greater, meaning at least 30% of the original grain has been polished away. The six main classifications of premium saké are as follows:

In general, the more the saké rice has been polished, the more refined and elegant the saké’s flavor profile will be. However, there can be a lot of overlap amongst the various premium saké classifications.

* (Note: Regulations regarding this minimum milling requirement have changed so that as long as the brewer uses only rice, water, and koji mold AND prints the seimaibuai on the label, the saké can be classified as junmaishu, even if the milling rate is less than 70%.)

Junmaishu

(june-my-shoe) “pure rice saké,” whose only ingredients are water, koji mold, and rice with a seimaibuai of at least 70% *. Junmai saké (the –shu suffix is usually dropped in conversation) tends to be more heavy and full-bodied than other types of premium saké, often with stronger, rice-influenced flavor and higher acidity. These qualities can make junmai saké easy to pair with a wide variety of food.

Honjozo

(hoan-joe-zoe) brewed with water, koji mold, and rice with a seimaibuai of at least 70%. During the brewing process, a small amount of pure distilled alcohol (“brewer’s alcohol”) is added. (See “Adding Brewer’s Alcohol: What difference can it make?”). Honjozo saké is often lighter and more fragrant than “pure rice” varieties, and can be quite easy to drink. (Don’t say we didn’t warn you . . .)

Junmai ginjoshu

(june-my-gin-joe-shoe, with the “gin” pronounced as in “gingham”) “pure rice premium saké,” brewed with only water, koji mold, and rice with a seimaibuai of at least 60% (40% of the original grain polished away). The brewing process for junmai ginjo saké is usually more labor intensive, since traditional tools and methods are used in conjunction with a longer fermentation at colder temperatures. Junmai ginjo saké tends to be light and refined, often with distinctively fruity aromas present.

Ginjoshu

(gin-joe-shu) like junmai ginjoshu, this saké is brewed using rice with a seimaibuai of at least 60%, but during the brewing process, a small amount of pure distilled alcohol is added. The brewing process for ginjo saké is usually more labor intensive, since traditional tools and methods are used in conjunction with a longer fermentation at colder temperatures. Ginjo saké tends to be light, refined and aromatic, often with distinctively fruity aromas present.

Junmai daiginjoshu

(june-my-die-gin-joe-shoe) “pure rice ultra-premium saké,” brewed with water, koji mold, and rice with a seimaibuai of at least 50% (50% of the original grain polished away). Junmai daiginjoshu is considered by many to be the peak of the saké brewing craft and a sublime embodiment of the brewmaster’s art. The brewing process for junmai daiginjo saké is even more labor intensive than other types, with traditional tools and precise methods being used in conjunction with a long, cold fermentation period. Very much “hands-on” brewing. Junmai daiginjo saké tends to be light and refined, with delicate, complex, and sophisticated flavors and elegant aromatics.

Daiginjoshu

(die-gin-joe-shoe) like junmai daiginjoshu, this saké is brewed using rice with a seimaibuai of at least 50%, but during the brewing process, a small amount of pure distilled alcohol is added. The brewing process for daiginjo saké is more labor intensive than other types, with traditional tools and precise methods being used in conjunction with a long, cold fermentation period. Very much “hands-on” brewing. Daiginjo saké tends to be light and refined, with delicate, complex, and sophisticated flavors and elegant aromatics.

Adding Brewer's Alcohol

What Difference Can It Make?

All the above classifications of premium saké that do not include the word junmai in their description are saké to which pure distilled brewer’s alcohol has been added during the brewing process, just before pressing.

While in lower grades of “regular” saké alcohol is often added in copious amounts to increase the brewer’s yield, in the premium saké grades honjozo, ginjo, and daiginjo, the addition of alcohol is strictly limited by law to a small amount (about 32 gallons for every 2200 pounds of rice used in brewing) for sound technical reasons.

Through trial and error, saké brewers discovered that many fragrant and flavorful components in the moromi (main mash) are soluble in alcohol. Adding a bit of alcohol after fermentation has completed, but before pressing to extract the saké from the lees, allows the brewer to pull these desirable components from the mash and retain them in them in the final product.

This small amount of added alcohol also lightens the flavor of the saké, which many feel can make the saké a bit more approachable.

Please note that the addition of alcohol during the brewing process does not make these types of saké “fortified,” because water is added later to bring the alcohol level down to that of other kinds of saké (approx. 15-16%).

While some drinkers have developed a prejudice against saké to which alcohol has been added, we feel that kind of thinking can only serve to limit one’s saké drinking experiences.

In the end, the addition of brewer’s alcohol is just another tool the toji (brewmaster) has at his disposal to help him exercise his skillful craft. Let your tastebuds be the judge!

Saké Meter Value

Higher is Drier

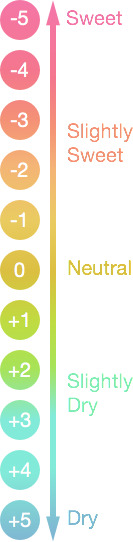

Though many things can affect whether a saké tastes sweet or dry (including acidity, serving temperature, mineral content of the brewing water, and previous dishes or accompanying food), one numerical guide that may be helpful, and can often be found on a bottle label, is the saké’s nihonshu-do or Saké Meter Value (SMV).

A saké’s SMV is its specific gravity; the density of the saké compared to the density of water. Theoretically, the higher (positive) the number, the drier the saké should taste. Conversely, the lower (more negative) the number, the sweeter the saké might taste. An easy way to remember this relationship is the phrase, “Higher is drier.”

While the SMV scale is generally seen in the -5 to +15 range, it’s important to remember that a saké’s SMV number is most useful and accurate in its extreme manifestations, and, as mentioned above, there are countless other factors affecting how one interprets sweetness and dryness.

Though traditional standards held that “real” saké was on the dry side, sweeter tasting saké has recently become more popular. Today’s average SMV hovers somewhere around +4.

In the end, the SMV is just one way for the consumer to get a general idea of how a saké might taste. No two palates are the same, however, and when it comes to evaluating and appreciating saké, there’s no substitute for experience. Kanpai to that!

Hours

Tuesday-Thursday: 2pm - 8pm

Friday-Saturday: 2pm - 10pm

Please follow us @ website, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram

Home

Saké Basics

Nomidachi News

Sake Nomi Events

Contact Us

Sake Nomi Copyright © 2016. All Rights Reserved

iBleedPixels Hand-crafted in Kochi City, Kochi Japan.